This Space Intentionally Left Ambiguous

If you tear a book apart at the spine you’ll find it’s comprised of signatures — groupings of 8, 16, or 32 pages layered one on top of another. Industrial printers throw ink onto huge sheets, which are then folded and cut such that the printed pages line up in reading order. If you begin with a sheet of paper big enough to hold 32 pages, but only have 30 pages of material to print on it, you’ll end up with two blanks. Hence the empty pages at the end of the book I just finished reading.

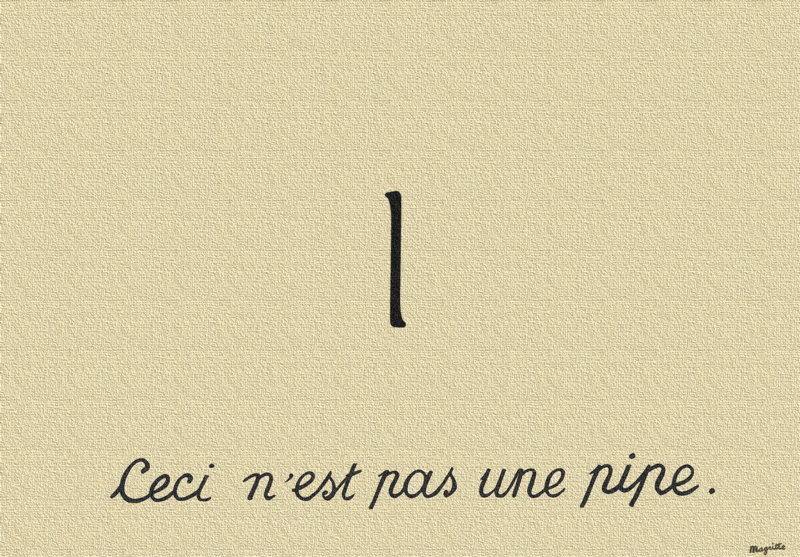

But sometimes it’s not immediately clear that the content is at an end. A technical manual doesn’t have a narrative arc or final chapter. It’s crucial for legal documents to be clear about exactly how much content they contain. When a blank page could be the difference between normal operation or catastrophic failure, how can we tell the difference between a printing error and End Of File? As a publisher, you have a convenient answer: the industry standard is a straightforward notice, “this page intentionally left blank.”

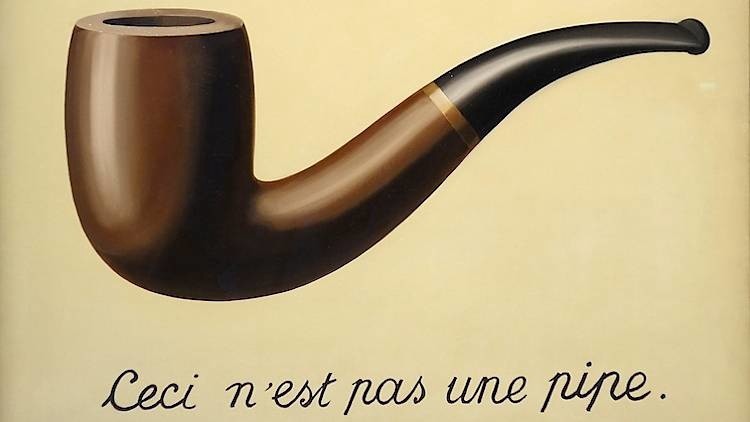

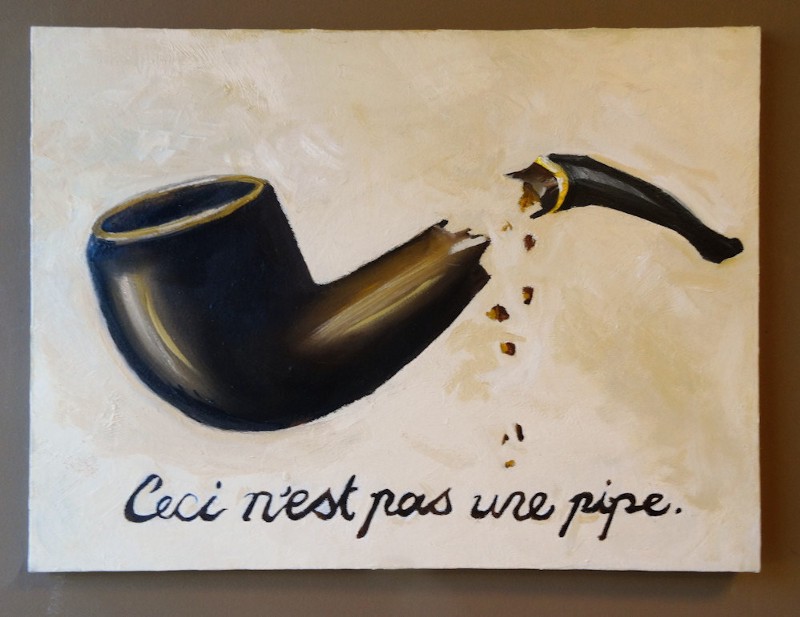

Only, no it isn’t. It has text printed on it, this page isn’t blank at all. As a matter of fact, this self-destructive motto poses a serious philosophical quandary, and worse, threatens to undermine a publisher’s reputation for honesty. If you’re willing to lie so blatantly about the blankness of a page with words printed on it in black and white, who knows how else you might be deceiving your readers? It should be a simple matter to sidestep this logical contradiction and print a more honest message conveying the same idea.

Not so fast, you may be in violation of the US Code of Regulations Section 47, §61.93 which mandates that blank pages in certain technical documents be marked as blank, with reckless disregard for the resultant paradoxes. Even worse, certain branches of the government threaten the reader for viewing the non-blank blank page in the first place, creating a legalistic Roko’s Basilisk:

[This page is intended to be blank. Please do not read it.]

Disastrous —if you read it. If, however, you do as the page advises, a new realm of possibilities is opened. If the page is left unread, isn’t it functionally blank? If a tree falls in a forest….

Niels Bohr supposedly answered this question (or a variant) when it was put to him by Albert Einstein, saying that there is no definite answer. The question cannot be proved either in the negative or the positive, because to have proof one would have to hear the tree falling/read the blank page, thus invalidating the premise that no one was around to hear it/I didn’t read that page officer I swear. This makes the blankness of the page a matter of faith rather than fact. While I can no longer convince you that the page you haven’t read is in fact blank, I ask you to join me in a leap of faith. Let’s choose to believe that the page we haven’t read is blank, and also not read it, just in case.

Now that we’ve built a firm philosophical foundation, let’s take this idea into the real world and try some application. Our first problem: we don’t know which pages we don’t know are blank, and which pages we know are not blank. That is, we can never tell, when we flip a page, whether a cease and desist notice is going to attack us. Our philosophical construction was secretly predicated on the knowledge of the page and its contents, despite our claims to not have read it. In reality, Blankist Existentialism only works when every page in the world is blank. If we read pages to check if they’re blank (and thus subject to BE) or not, we run the risk of legal action, and also invalidate the faith required to be a true Blankist.

Better to just not read any pages at all, and stick to e-books.

[This paragraph intentionally left unused.]